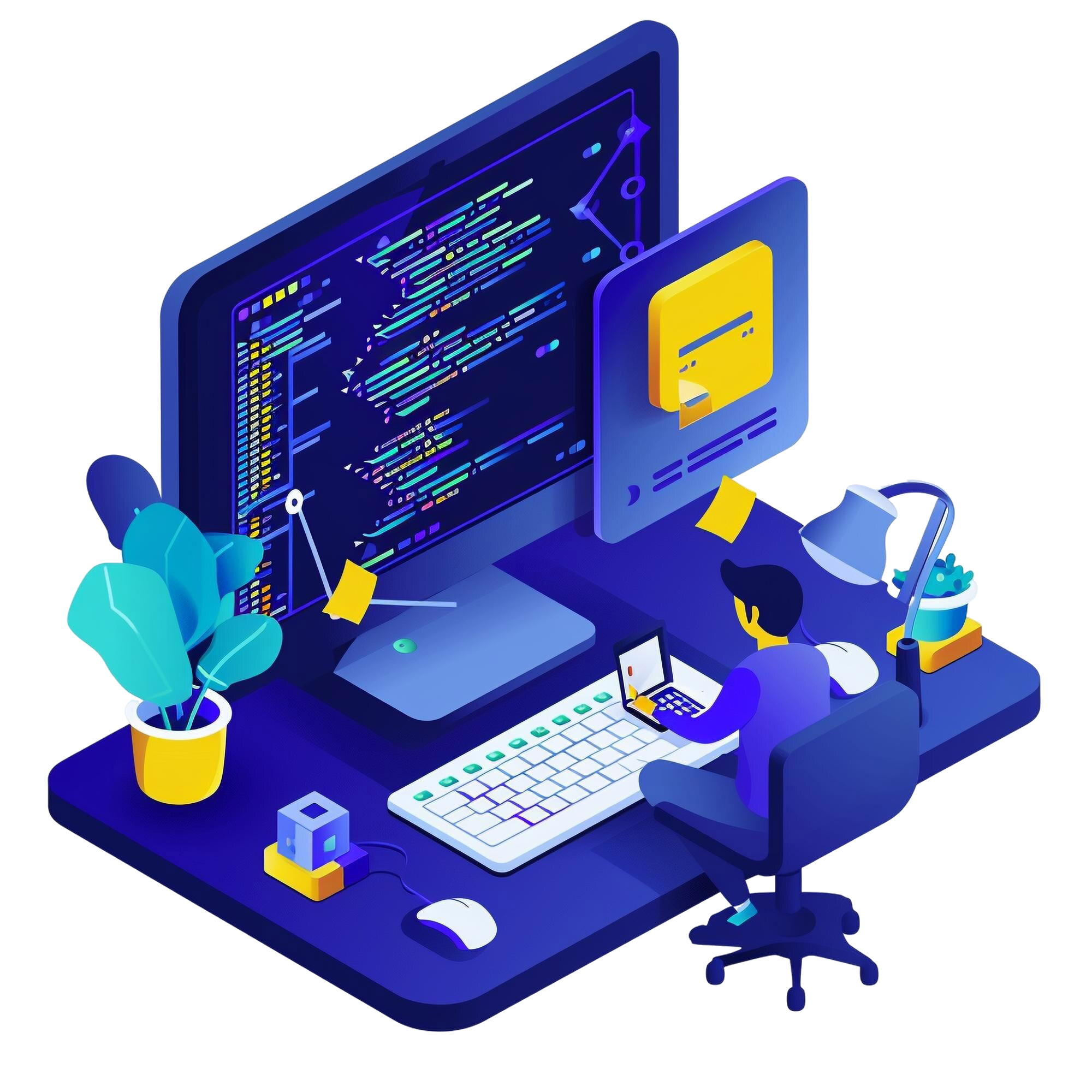

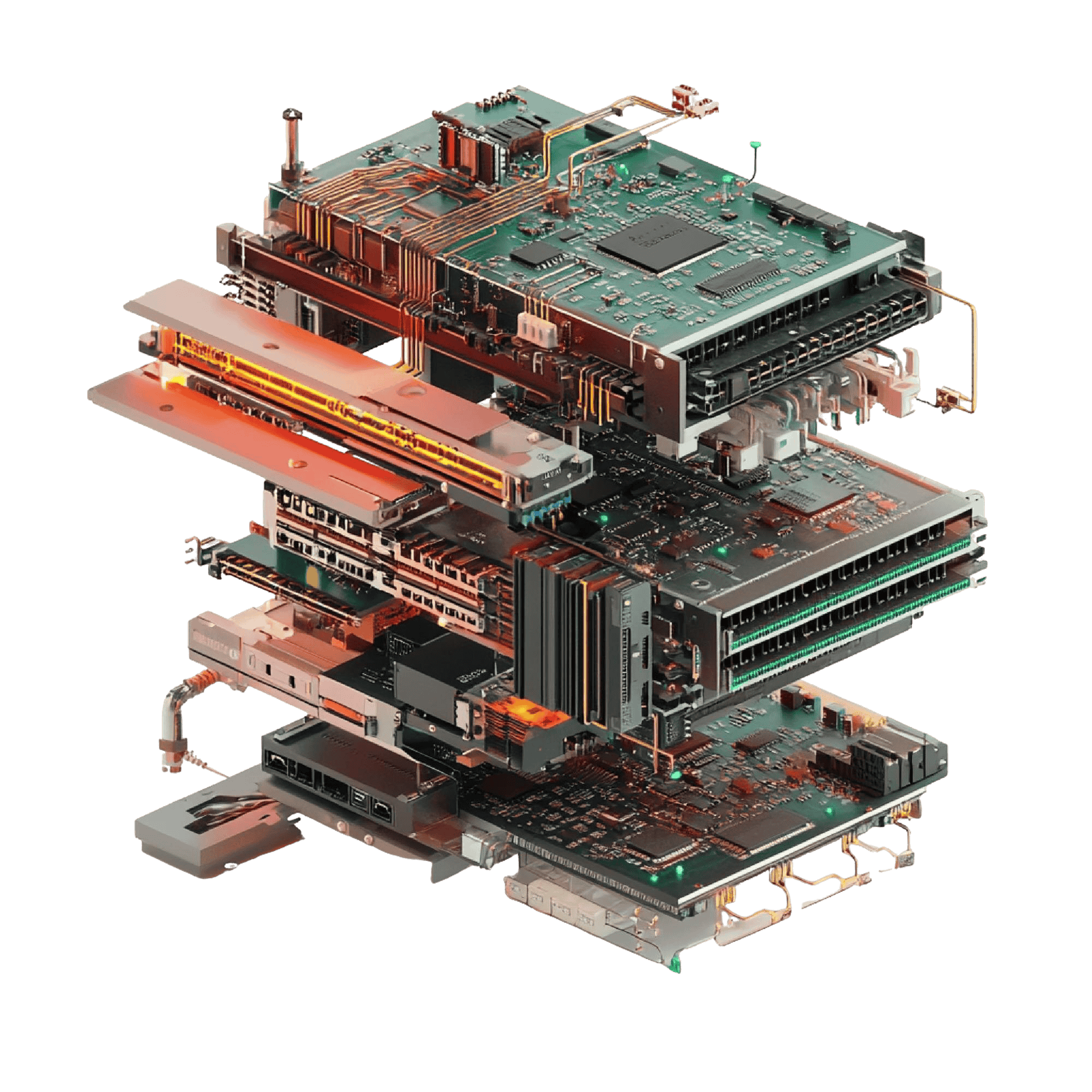

About Us

We transform businesses through innovative solutions and expert guidance.

At Stacks & Breaks, we bridge the gap between complex technology challenges and practical business solutions. Our team of seasoned experts combines deep technical knowledge with strategic business acumen to deliver transformative results. From Fortune 500 companies to emerging startups, we've helped organizations across industries leverage technology to achieve their most ambitious goals.

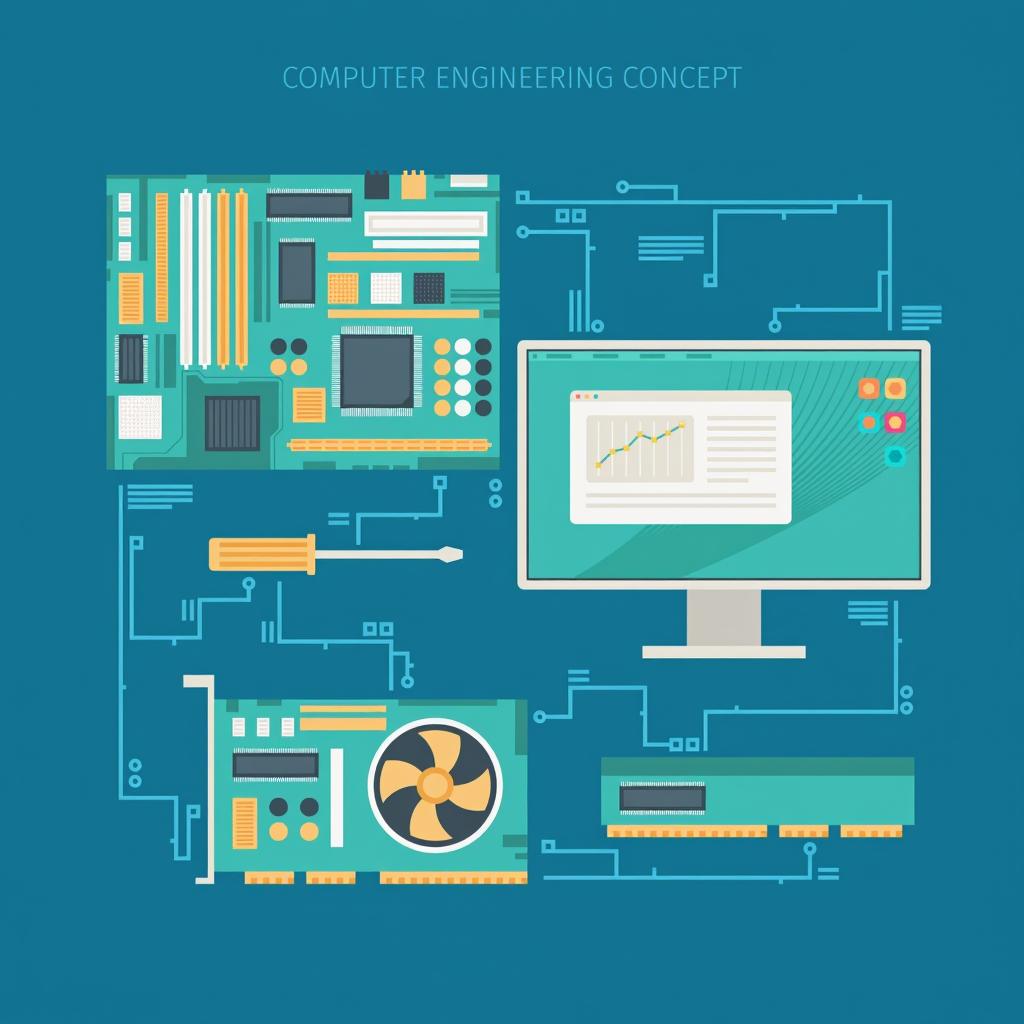

Recognized leader in technology consulting and driver development

Recognized leader in technology consulting and driver development Certified professionals with decades of combined experience

Certified professionals with decades of combined experience Cutting-edge solutions that drive competitive advantage

Cutting-edge solutions that drive competitive advantage